CAUTION FOR EARTH: AN EPIC JOURNEY THROUGH THE AGES

So, how long have we been caring about the Earth crisis?

Public consciousness relating to caring for the Earth has been said to have come in with the environmental movement.

Some say this movement began in the late 19th century and became a mass movement in the 1960s.

Well, let’s check that out…

We might remember the publication in 1962…

of Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring, which remains credited by many as the catalyst that launched the environmental movement.

Or perhaps we knew about—or possibly were among the…

Youth in the environmental movement in the 1960’s. who were asking: “DON’T YOU SEE WHAT’S GOING ON?”

Their placard depicts a burning Earth, centered in an eye

and many of us may remember that…

the first Earth Day was celebrated on

April 22, 1970.

NYT Headline:

Milliions Join Earth Day Observances Across the Nation

View is north from 42nd St., with Central Park in background

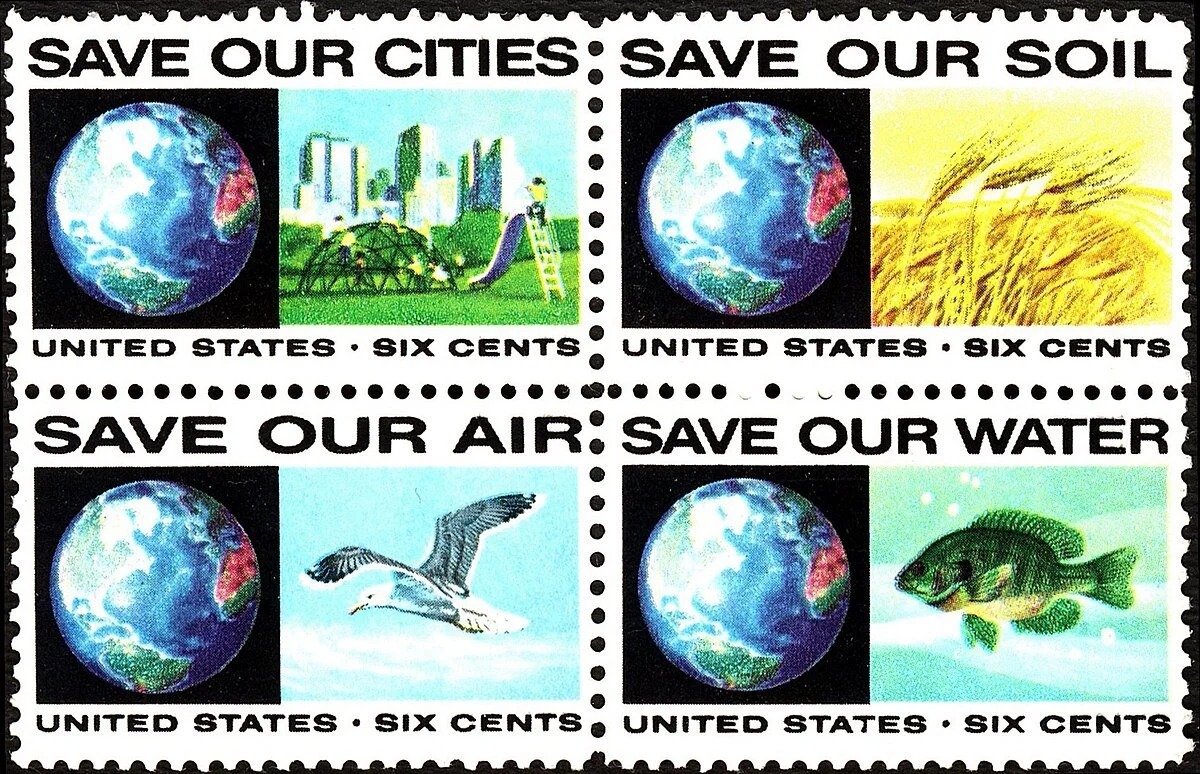

And, we also might have used—or perhaps collected…

The U.S. Post Office’s products of its own weighing in. This is the 1970 issue of a four-stamp set that focused attention on the need for pollution control.

It made it clear that only a massive effort would help in solving the perilous pollution problems in our air, water, soil, and cities.

The 19th century stage, of course, was way before our time.

The conservation movement that was in evidence in the late 19th century was a reaction to the environmental degradation that resulted from the industrial revolution.

All of these moments of relatively recent activism in the environmental movement have been positive, and yet…

there is evidence that the years of environmental awareness actually stretch back far beyond those fairly recent times.

The organization Greenpeace has on its website (Greenpeace.org) an article that was written by its co-founder Rex Weyler.

Weyler’s article, “A Brief History of Environmentalism,” is a comprehensive history that shows the roots of the movement extending much farther back than the 19th century.

His article is on his own website at www.rexweyler.ca, as well.

I have reprinted a truncated version of Rex Weyler’s article below.

For your ease in perusing it quickly, and to put a “face” on this environmental movement of many years, I have embellished the essay with bolding and photographs.

For Rex Weyler’s full article, click the link in its title below.

A Brief History of Environmentalism

"The goal of life is living in agreement with nature."

— Zeno ~ 450 BC (from Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers)

by Rex Weyler, 5 January 2018

Awareness of our delicate relationship with our habitat likely arose among early hunter-gatherers when they saw how fire and hunting tools impacted their environment.

Anthropologists have found evidence of human-induced animal and plant extinctions from 50,000 BCE [late Paleolithic Era], when only about 200,000 Homo sapiens roamed the Earth.

We can only speculate about how these early humans reacted, but migrating to new habitats appears to be a common response.

Ecological awareness first appears in the human record at least 5,000 years ago.

Vedic sages praised the wild forests in their hymns, Taoists urged that human life should reflect nature’s patterns and the Buddha taught compassion for all sentient beings.

In the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh, we see apprehension about forest destruction and drying marshes. When Gilgamesh cuts down sacred trees, the deities curse Sumer with drought, and Ishtar (mother of the Earth goddess) sends the Bull of Heaven to punish Gilgamesh

In ancient Greek mythology, when the hunter Orion vows to kill all the animals, Gaia objects and creates a great scorpion to kill Orion. When the scorpion fails, Artemis, goddess of the forests and mistress of animals, shoots Orion with an arrow.

Some of the earliest human stories contain lessons about the sacredness of wilderness, the importance of restraining our power, and our obligation to care for the natural world.

Early environmental response

Five thousand years ago, the Indus civilisation of Mohenjo Daro (an ancient city in modern-day Pakistan), were already recognising the effects of pollution on human health and practiced waste management and sanitation.

Mohenjo Daro

In Greece, as deforestation led to soil erosion, the philosopher Plato [427-347 BCE] lamented, “All the richer and softer parts have fallen away, and the mere skeleton of the land remains.”

Plato

Communities in China, India, and Peru understood the impact of soil erosion and prevented it by creating terraces, crop rotation, and nutrient recycling.

The Greek physicians Hippocrates [460-375 BCE] and Galen [129-216 CE] began to observe environmental health problems such as acid contamination in copper miners. Hippocrates’ book, De aëre, aquis et locis (Air, Waters, and Places), is the earliest surviving European work on human ecology.

Hippocrates

Galen

In 1306, the English King Edward I [1239-1307] limited coal burning in London due to smog. In the 17th century, the naturalist and gardener John Evelyn [1620-1706] wrote that London resembled “the suburbs of Hell.” These events inspired the first ‘renewable’ energy boom in Europe, as governments started to subsidise water and wind power.

King Edward I

John Evelyn

In the 16th century, the Dutch artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder [died 1569] painted scenes of raw sewage and other pollution emptying into rivers, and Dutch lawyer Hugo Grotius [1583-1645] wrote The Free Sea, claiming that pollution and war violate natural law.

Netherlandish Proverbs (1559) - Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

If you look closely at the mid-ground to the right, you can see a wealthy man dumping money into the sewage.

Hugo Grotius

Environmental rights

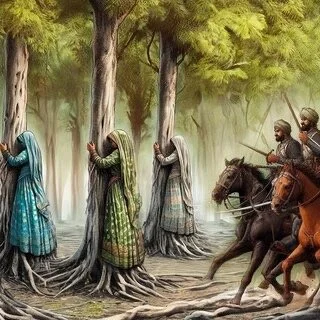

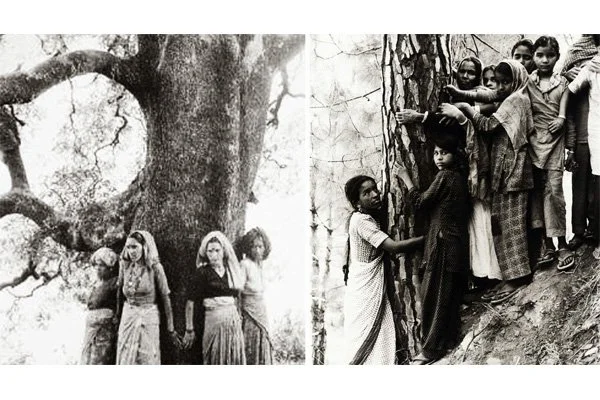

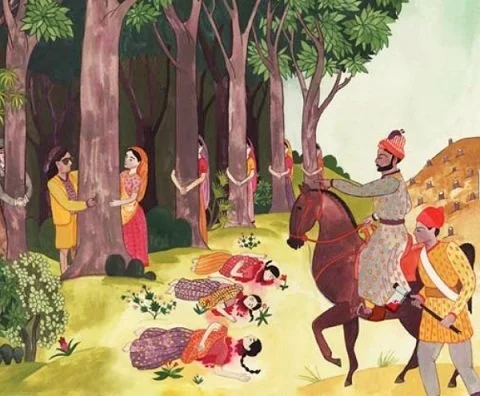

Perhaps the first real environmental activists were the Bishnoi Hindus of Khejarli, who were slaughtered by the Maharaja of Jodhpur in 1720 for attempting to protect the forest that he felled to build himself a palace.

The Massacre of the Bishnoi, a Hindu sect known for their reverence of nature

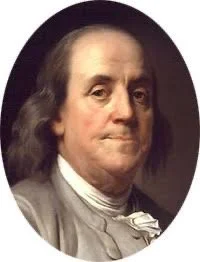

The 18th century witnessed the dawn of modern environmental rights. After a yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia, Benjamin Franklin [1706-1790] petitioned to manage waste and to remove tanneries for clean air as a public “right” (albeit, on land stolen from Indigenous nations).

Ben Franklin

Later, American artist George Catlin [1796-1872] proposed that Indigenous land be protected as a “natural right.”

George Catlin

Knowledge of global warming began 200 years ago, when Jean Baptiste Fourier [1768-1830] calculated that the Earth’s atmosphere trapped heat like a greenhouse.

Jean Baptiste Fourier

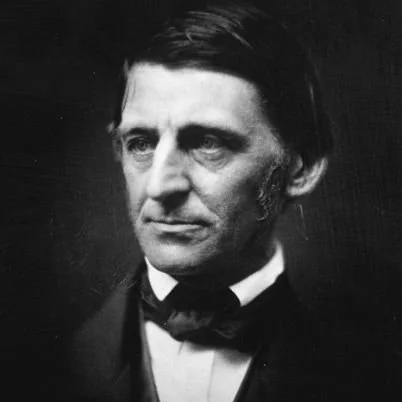

Then, in 1835, Ralph Waldo Emerson [1803-1882] wrote Nature, encouraging us to appreciate the natural world for its own sake and proposing a limit on human expansion into the wilderness.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

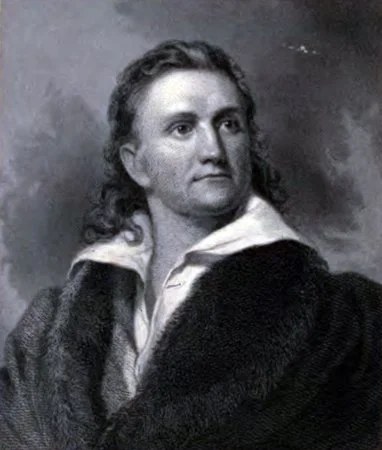

American Botanist William Bartram [1739-1823] and ornithologist James Audubon [1785-1851] dedicated themselves to the conservation of wildlife.

William Bartram

John James Audubon

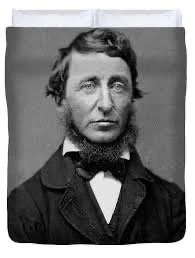

Henry David Thoreau [1817-1862] wrote his seminal ecological treatise, Walden, which has since inspired generations of environmentalists.

Henry David Thoreau

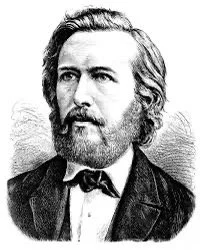

A few decades later, George Perkins Marsh [1801-1882] wrote Man and Nature, denouncing humanity’s indiscriminate “warfare” upon wilderness, warning of climate change, and insisting that “The world cannot afford to wait” – a plea we still hear today.

George Perkins Marsh

At the end of the 19th century, in Jena, Germany, zoologist Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919) wrote Generelle Morphologie der Organismen in which he discussed the relationships among species and coined the word ‘ökologie’ (from the Greek oikos, meaning home), the science we now know as ecology.

Ernst Haeckel

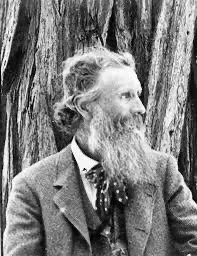

In 1892, John Muir [1838-1914] founded the Sierra Club in the US to protect the country’s wilderness. Seventy years later, a chapter of the Sierra Club in western Canada broke away to become more active. This was the beginning of Greenpeace.

John Muir

Greenpeace started in 1971 in British Columbia with a small group of volunteer activists who organized a music concert to raise funds to sail a boat from Vancouver to Amchitka Island in Alaska to protest against US militarism and the testing of nuclear weapons.

Greenpeace

Environmental action

That land is a community is the basic concept of ecology,” wrote Aldo Leopold [1887-1846] in A Sand County Almanac, “but that land is to be loved and respected is an extension of ethics … a thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.”

Aldo Leopold

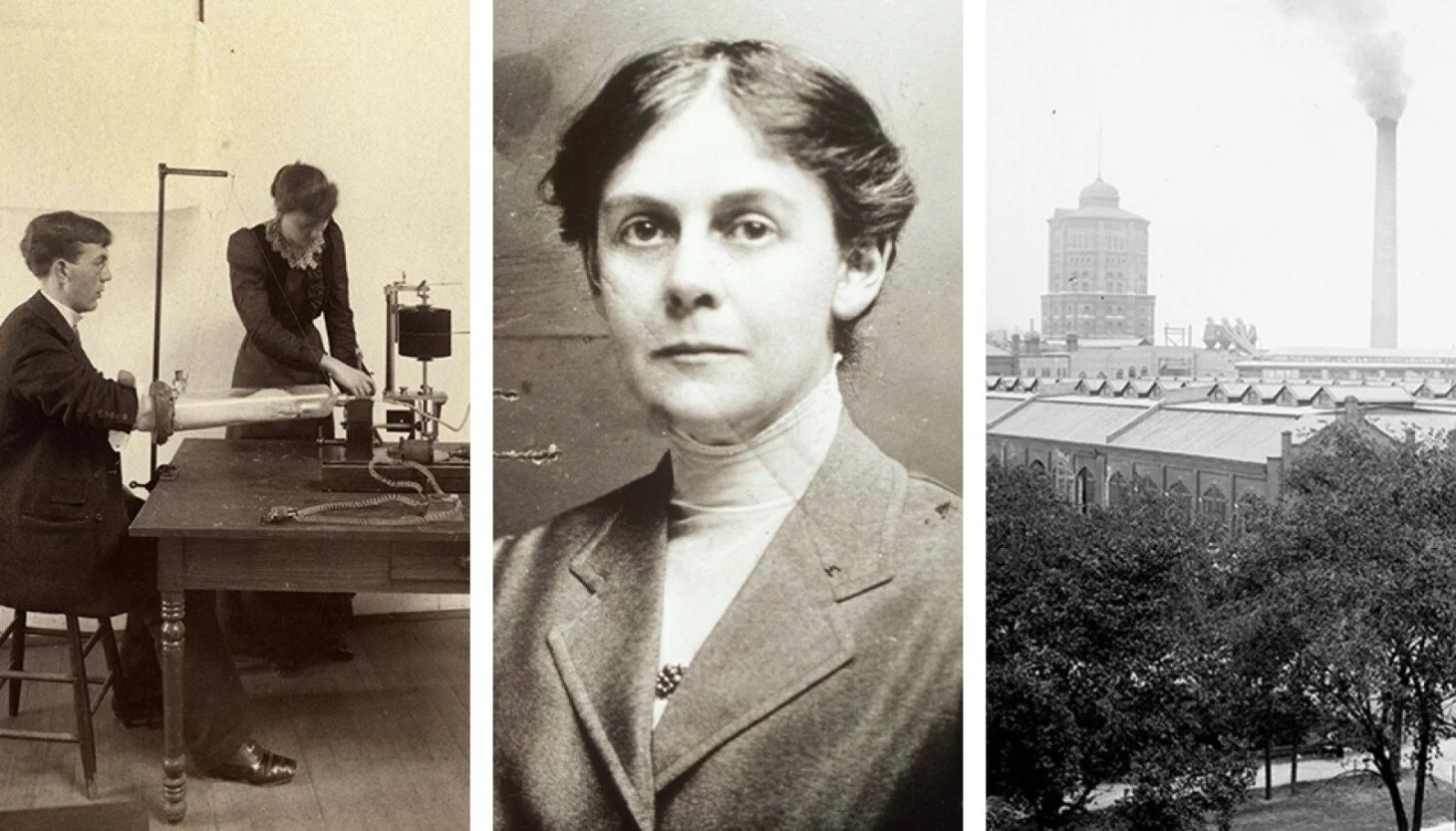

In the early 20th century, the [American] chemist Alice Hamilton [1869-1970] led a campaign against lead poisoning from leaded gasoline, accusing General Motors of willful murder. The corporation attacked Hamilton, and it took governments 50 years to ban leaded gasoline.

Alice Hamilton

Meanwhile, industrial smog choked major world cities. In 1952, 4,000 people died in London’s infamous killer fog, and four years later the British Parliament passed the first Clean Air Act.

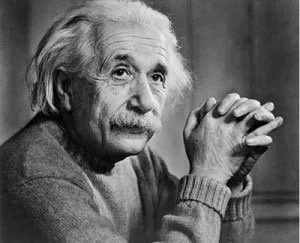

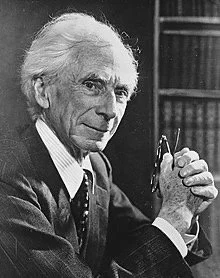

Ecology grew into a full-fledged, global movement with the development of nuclear weapons. Albert Einstein [1879-1955], who felt morally troubled by his contribution to the nuclear bomb, drafted an anti-nuclear manifesto in1955 with British philosopher Bertrand Russell [1872-1970], signed by ten Nobel Prize winners.

The letter inspired the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, in the UK – a model for modern, non-violent civil disobedience.

Albert Einstein

Bertrand Russell

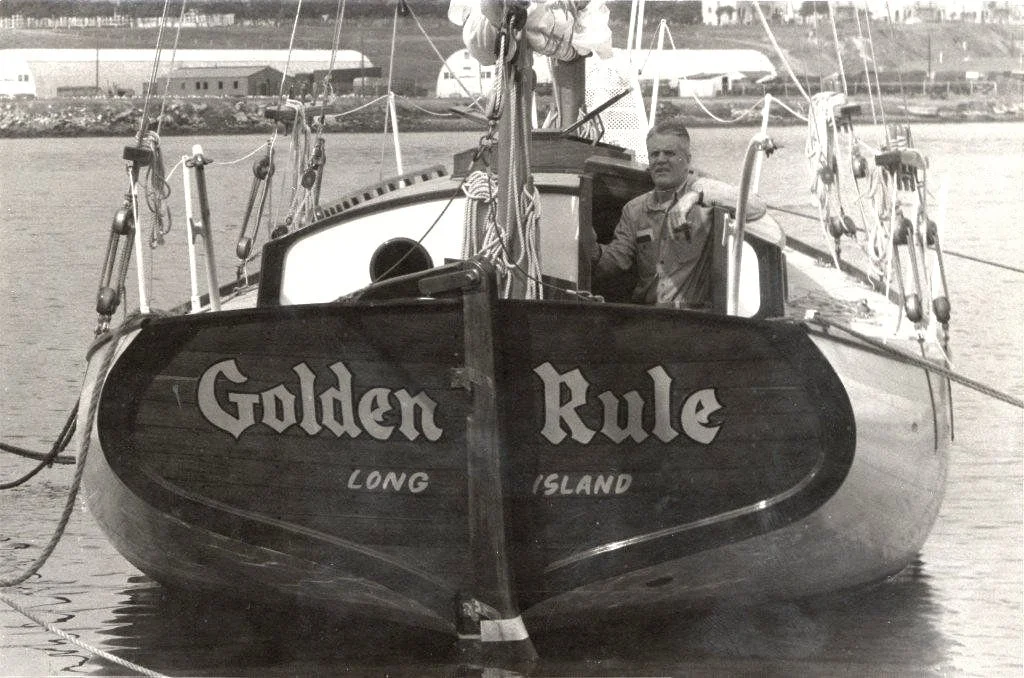

In 1958, the Quaker Committee for Non-Violent Action launched two boats – the Golden Rule and [the] Phoenix – into US nuclear test sites, a direct inspiration for Greenpeace a decade later.

The Golden Rule: the First Protest Ship

Rachel Carson [1907-1964] brought the environmental movement into focus with the 1962 publication of Silent Spring, describing the impact of chemical pesticides on biodiversity. “For the first time in the history of the world,” she wrote, “every human being is now subjected to contact with dangerous chemicals.”

Shortly before her death she expressed the emerging ecological ethic in a magazine essay: “It is a wholesome and necessary thing for us to turn again to the Earth and in the contemplation of her beauties to know the sense of wonder and humility.”

Rachel Carson

Norwegian philosopher Arne Næss [1912-2009] cited Silent Spring as a key influence for his concept of ‘Deep Ecology’ – ecological awareness that goes beyond the logic of biological systems to a deep, personal experience of the self as an integrated part of nature.

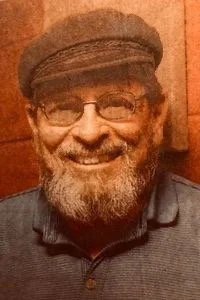

In The Subversive Science, Paul Shepard [1925-1996] described ecology as a “primordial axiom,” revealed in ancient cultures, which should guide all human social constructions. Ecology was “subversive” to Shepard because it supplanted human exceptionalism with interdependence.

Paul Shepard

In India, villagers in Gopeshwar, Uttarakhand, inspired by Gandhi and the 18th century Bishnoi Hindus, defended the forest against commercial logging by encircling and embracing trees.

Their movement spread across northern India, known as Chipko (“to embrace”) – the original tree-huggers

Gopeshwar, India

The Chipko Movement in India

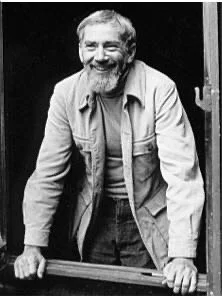

In 1968, the American writer Cliff Humphrey [1937-2024] founded Ecology Action. One media stunt involved Humphrey gathering 60 people in Berkeley, California, to smash his 1958 Dodge Rambler into the street, declaring, “these things pollute the earth.”

Prophetically, Humphrey told Greenpeace co-founder Bob Hunter [1941-2005] , “This thing has just begun.”

Cliff Humphrey

A year later, inspired by the writings of Carson, Shepard, and Næss, and by the actions of Chipko and Ecology Action, a group of Canadian and American activists set out to merge peace with ecology, and Greenpeace was born.

Nearly a half-century after the foundation of Greenpeace, the global ecology movement has reached every corner of the world, with thousands of groups springing up to defend the environment.

Meanwhile, the challenges facing us grow ever more daunting. The next half-century will test whether or not humanity can respond to the challenge.

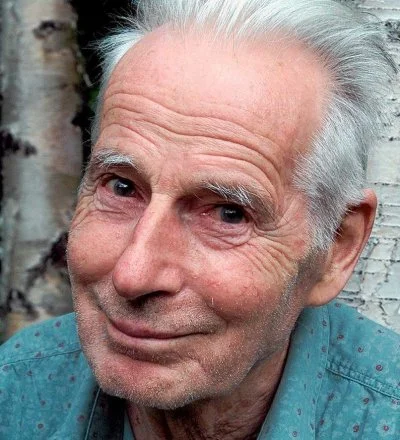

Rex Weyler [1947- ] is an author, journalist and co-founder of Greenpeace International.

Rex Weyler

We, at C:WED, hope and pray that humanity will pass the test, as Rex Weyler has articulated it—and that conscious awareness, belief, motivation, and action will actually take place sooner, rather lhan later.

Might we dare trust that the “thousands of groups springing up to defend the environment” could help shorten the time span for humanity to fully respond to the challenge?

I, Anne, believe that climate crisis denialism is rooted in greed, both personal and corporate—in a desire for the acquisition of wealth and material goods, as well as for the attainment of power and status. And it is rooted, perhaps, also in vanity, the turning inward that prioritizes one’s self.

“Vanitas, vanitatum, dixit Ecclesiastes; Vanitas vanitatum et omnia vanitas.” (Latin)

“Vanity of vanities, says the Teacher; Vanity of vanities and all is vanity.” Ecclesiastes 12:8 (NSRV)

One translator identifies the verse as a cautionary message for the reader: that the acquisition of wealth and worldly possessions is mere vanity.

Vanitas Vanitatum”, Painted by Brother Jens Rusch

Recall this entry in Rex Weller’s essay above:

“Perhaps the first real environmental activists were the Bishnoi Hindus of Khejarli, who were slaughtered by the Maharaja of Jodhpur in 1720 for attempting to protect the forest that he felled to build himself a palace'.”

Might the Maharaja’s motive be an example of ecological “Vanitas vanitatum?”

And for today, do our priorities matter?

…to be continued

as we look for inspiration in the next few posts

to specific efforts by some relatively recent

individual environmental activists

IN YOUR OWN WORDS:

Preview of current post: “EARLY CAUTION FOR THE EARTH: Beyond the Beyond” by Anne Andersson, July 1, 2025

—I really liked the post you sent! So important! 🌍 🌎 🌏

“The Story of Stuff”

“The Story of Stuff” with Annie Leonard. This video may be a bit old (16 years ago) but I still think it is relevant and provides an excellent overview/insight/explanation of how our consumption affects the planet. 🥰 —M.A.

Re: Previous post: “America, the Beautiful”

—Thank you. What a wonderful inspiration for our Independence Day. Happy 4th. —R.E.

—Beautiful. Enjoyed. Thank you, Anne. —E.

—Beautiful pictures. Happy 4th to you ladies. —P.H.

— Just beautiful! Filled with awe. Loved the brother/sisterhood too. —L.C.

—Thank you thank you! Fascinating to know of these stories. Blessings. —K.E.M.

C:WED Wish List:

—If you have any environmentalists whom you would like to highlight, please send their stories along to us at info@cwed.org.

or

Please remember us when you are considering a contribution! Every donation helps keep us technologically alive.