THE PERSONAL IS POLITICAL - a gift of insight from Second-Wave Feminism

What does this mantra mean?

Interpretation is the key!

“The Personal is Political” has been used in several movements, and it has been attributed to a variety of sources.

For the feminist movement, it is the interpretation of its two obvious points that I consider to be significant:

Political: How is the word “political” defined in the context of this expression?

Personal: What part does the relationship between the private and public spheres play?

On the first point, Carol Hanisch has often been credited with originating the slogan because she wrote an essay in February 1969 entitled “The Personal is Political.“ She updated it in 2006.

Hanisch said she used political in the “broad sense of the word—as having to do with power relationships—not in the narrow sense of electoral politics.”

And the power relationships to which she was referring were those between women and men.

Hanisch was not the only one.

In her book Sexual Politics (published January 1, 1970), Kate Millett developed the theory that for women, the personal is political, broadening the term politics to include all “power-structured relationships.”

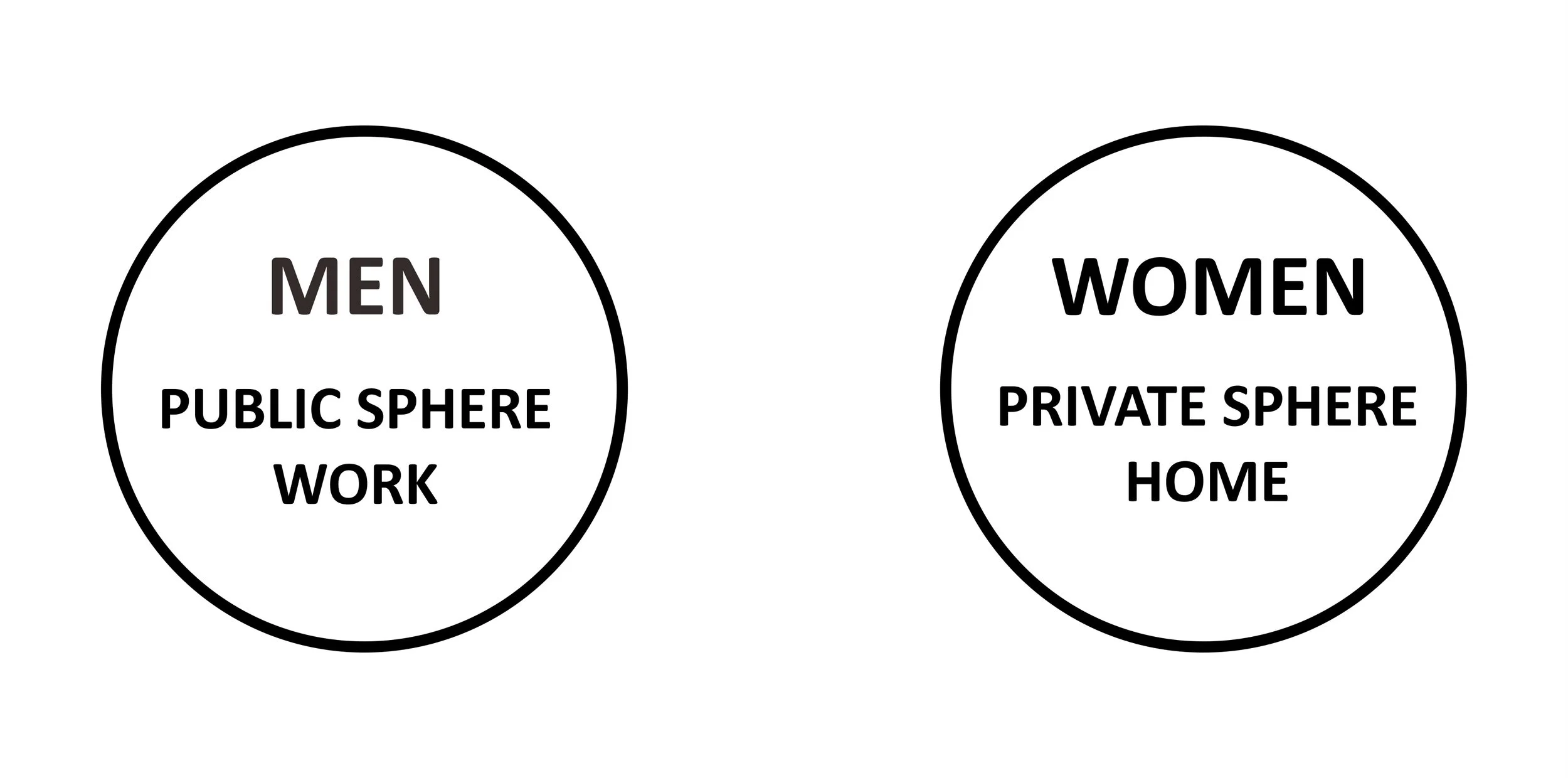

The second point is associated with altering the relationship between the public and private spheres.

For centuries, both spheres had been considered separate; neither was related to the other nor did either influence the other. (1)

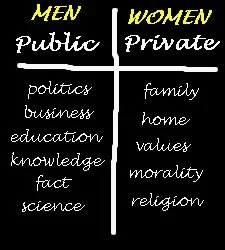

The public domain, which was held to be the territory of men, was the place for government rule and law, and for public discourse.

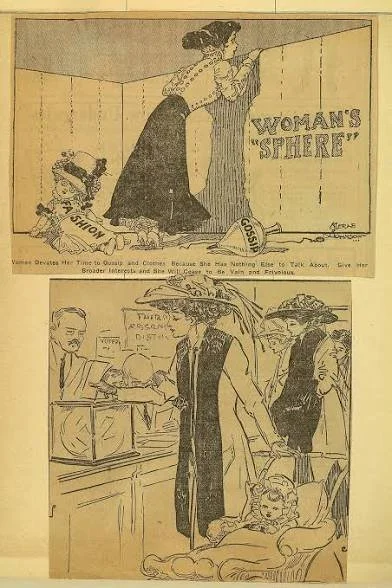

The private realm of the family (women’s assigned territory in the home) was virtually unknown to the public sphere and was untouchable by government rule and law.

In common parlance, what went on in private, remained private. ”Don’t air dirty laundry in public,” as the saying goes.

As such, looking in from the outside, there was a tacit understanding that in the private sphere, there was a fair amount of freedom. These included freedom of choice and freedom from the dominant power of the government and the law as it operates in the public realm.

(Note: this post is reporting on the perspective of American white women.)

Feminists disagreed that the privacy in the family was actually that free for both women and men.

The format of the traditional family as it existed in the 1960s and 1970s, for example, was that of the paterfamilias (refers to the tradition of male authority within the Roman household, as well as Roman society in general).

In that format of the paterfamilias, only men had those freedoms.

Women did not have freedom of choice, in that they were obligated to perform the myriad household duties of the housewife.

Relations between men and women in many households were based on power. In some, they still are.

Within the paterfamilias, the man dominates the woman, and wherever there is domination, there is hierarchy—and power.

I will add that neither was men’s private-sphere freedom from the law of benefit to women.

Were the marriage to turn abusive, there were no consequences for the perpetrator.

Second-wave feminism posed a solution to the power imbalance within the family of that time.

Feminists wanted to change the relationship existing between the private and the public spheres; hence, “the personal is political.”

That concept change would bring the principles of justice, as they exist in the public sphere, actively into the private. Thus, the private sphere would have to become open to the scrutiny of the law.

Now, who was going to call out the oppression of women in a marriage, so that this justice could be applied?

Certainly not the men. As the holders of power, men surely did not wish to relinquish any of it.

On two different occasions, months apart in the late 1970s, in discussions about feminism with two different men, I witnessed their displeasure.

One responded with alarm, stating emphatically that he did not want to wash dishes.

The other was also concerned about dishes: I heard him tell his friend to be sure not to be the one to load the dishwasher in their new home!

Worry about dishwashing has come up frequently enough to lead me to wonder if it has become, particularly for those men, an implicit metaphor for their fear—the fear of loss of benefits that their position of marital power had afforded them?

So, it was up to the women to do the telling.

Women, however, initially needed to become aware of a well-hidden fact: that their own situations were not theirs alone, but rather existed and operated as part of a system that was larger than themselves.

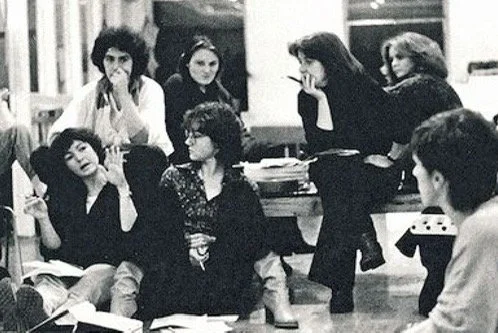

Here is where the Consciousness-Raising (C-R ) groups of the late 1960s and 1970s came into play.

These groups, designed by radical feminists in the movement, were rising up across the country. They filled the role of waking women up to what was going on.

They were doing it simply by giving women a format for discussing a series of questions and how they related to the women’s lives.

(See my previous post, “The Art of Waking Up into Second-Wave Feminism,” for a detailed description of the C-R group, in which I participated.

When women met together in these groups and discussed their own lived situations, it helped them become aware of the politics collectively operating in their lives. And so they could advocate for better conditions, especially within the family.

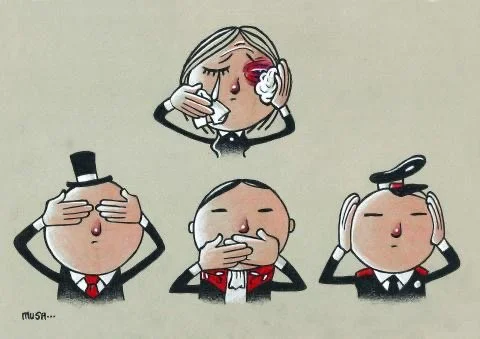

I would say that another outcome of this feminist thinking, that the personal is political, was the naming—as domestic violence—the abuse of power of a husband over his wife, as well as the bringing of it from the private out into the open of the public sphere. The dirty laundry was out.

It also recognized that a wife’s calling it out for what it is, was not only okay, but extremely important. It could save lives.

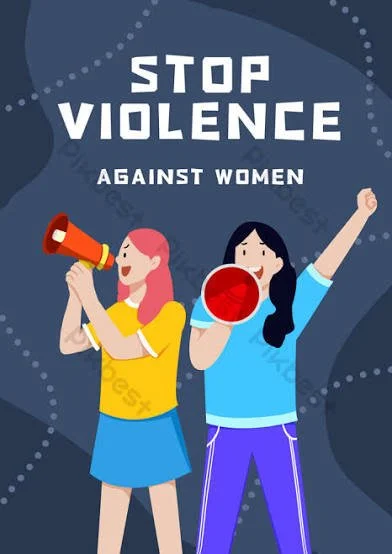

And with laws against domestic violence reaching into the private sphere, husbands could be held liable for wife-beating or wife-rape.

As we well know, at this point in time in the 21st century, and for years before this, certain personal happenings within the private sphere of the family have become public knowledge—and domestic violence is now recognized as a reality!

For example, in 1994 the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) was passed to prevent gender-based violence.

However, for all the power gained with women’s speaking out, there were fractures within the second-wave feminist movement. These related to degrees of radicalism, race, and priority of issues, especially as critiqued by women of Third-World countries.

A decent summary about the slogan “the personal is political” is found in this entry in the online Encyclopedia Brittanica. It was written by Christopher J. Kelly and fact-checked by the editors.

That link will also lead to a herstory of feminist activism and descriptions of the different waves of feminism, including the fractures that developed within them.

____________________________

In closing, let’s loop back to the family to take a look at where these power dynamics might have been initiated.

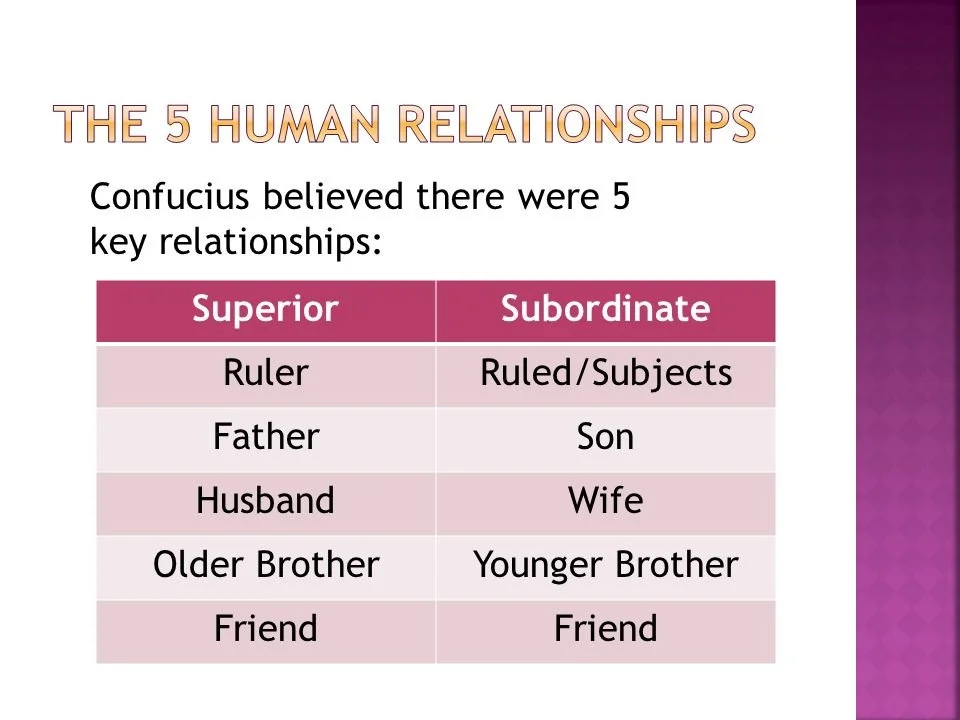

The personal as a political force (political in the sense that Hanisch and Millett have used it) is a significant part of the Confucian and Aristotelian relationship codes that still influence society today.

Confucius, the Chinese philosopher (551-479 BCE) identified these relationships of power:

The Greek philosopher Aristotle (384-322 BCE) wrote in his Politics: “the male is by nature superior and the female inferior, the male ruler and the female subject.

And so, there we have part of the picture of gender domination, all of which operate under the umbrella of the 5000-year old system of patriarchy.

Gerda Lerner defined patriarchy this way in her 1986 book, The Creation of Patriarchy:

Patriarchy in its wider definition means the manifestation and institutionalization of male dominance over women and children in the family and the extension of male dominance over women in society in general. It implies that men hold power in all the important institutions of society and that women are deprived of access to such power.

Here is a question to ponder:

What might have been the rules under which girls would have been raised in a traditional family of the past?

Note: Girls of today could be raised in a similar way under the Tradwife (combo of “traditional wife” or “traditional housewife”) movement, which has been rising up recently.

A tradwife is a woman who believes in and practices traditional gender roles and marriages.

Answer to the question:

Fom Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s 1762 treatise, Emile; or, On Education:

Thus the whole education of women ought to be relative to men. To please them, to be useful to them, to make themselves loved and honored by them, to educate them when young, to care for them when grown, to council them, to console them, and to make life agreeable and sweet to them—these are the duties of women at all times, and should be taught them from their infancy.

…To be continued.

_______________________________

Note:

We will pause posting, for next week only, as we enter into the Christian celebration of Easter.

As we say in our origins statement, C:WED begins from our own Christian tradition, while respectfully honoring other religious faiths.

Happy Spring!

Blessed Resurrection Day!

Joyous Passover!

Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org)“Private Sphere”

Resources:

—King, Kathryn R. (1995). "Of Needles and Pens and Women's Work". Tulsa Studies in Women's Literature.

—Vickery, Amanda (1993). "Golden age to separate spheres? A review of the categories and chronology of English women's history" (PDF). The Historical Journal.

—Tétreault, Mary Ann (2001). "Frontier Politics: Sex, Gender, and the Deconstruction of the Public Sphere". Alternatives: Global, Local, Political.

—May, Ann Mari (2008). "Gender, biology, and the incontrovertible logic of choice". The 'woman question' and higher education: perspectives on gender and knowledge production in America. Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 39.

—Peterson, V. Spike (2014-07-03). "Sex Matters". International Feminist Journal of Politics.

—Wells, Christopher (2009). "Separate Spheres". In Kowaleski-Wallace, Elizabeth (ed.). Encyclopedia of feminist literary theory. London, New York: Routledge. p. 519.

—Adams, Michele (2011). "Divisions of household labor". In Ritzer, George; Ryan, J. Michael (eds.). The concise encyclopedia of sociology. Chichester, West Sussex, U.K.; Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 156–57.

—J. Childers/G. Hentzi ed., The Columbia Dictionary of Modern Literary and Cultural Criticism(1995) p. 252.

C:WED Wish List:

—Please remember us when you are thinking of making a charitable contribution.

—Do send us something related to our themes:

Women, the Earth, and/or the Divine.

—Maybe a quote, a poem, a prayer, a cartoon, a photo or video, a drawing or painting, or your own original essay?

A resource recommendation?

Or just a comment?