THE WOMAN’S BIBLE Third-Wave Feminists Continue First-Wave Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s Work!

Why did some feminists push Elizabeth Cady Stanton out of active involvement within a women’s suffrage association at the tail-end of the nineteenth century?

This happened because she had done what some adversaries thought was politically dangerous.

Cady Stanton had called together a group of women who were committed to writing a revisionary commentary on the Bible. The committee had singled out sections within the Bible that were misogynistic and sexist in their interpretations—and in the text itself.

Even worse, this revising committee, as they called themselves, published their critical comments in a book and entitled it: The Woman’s Bible.

And worst of all, the book became a bestseller of its time.

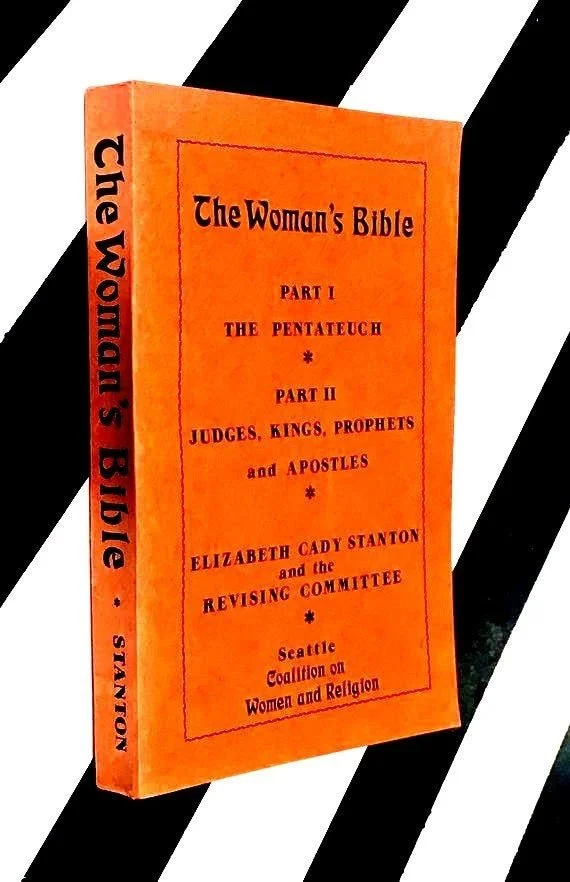

Title Page—Part One

The Woman's Bible is a collection of essays and commentaries on the Bible compiled in 1895 [and 1898] by a committee chaired by Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815-1902), who had been one of the organizers of the Seneca Falls Convention (the first Woman's Rights Convention held in 1848) and was a founder of the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA).

Cady Stanton’s purpose was to initiate a critical study of biblical texts that were being used to degrade and subject women in order to demonstrate that it was not divine will that humiliates women, but human desire for domination.

—Harvard Divinity School Library, Cambridge, MA

Preface

Preface, continued

[The revising committee] excerpted and commented on those portions of the Bible in which women appear—or are conspicuously absent. In their comments the authors [criticized] both the male bias that had distorted the interpretation of the Bible and the misogyny of the text itself.…

Many of [the committee’s] observations, which seemed so daring at the time, have since come to be widely held, even treated as obvious.

—Women’s Bible Commentary, Introduction to the first edition. Westminster John Knox Press, 1992.

In her introduction to The Woman’s Bible, Cady Stanton noted that many people used the Bible against women’s rights advocates.

Clergy, legislators, and the press all cited the Bible to justify the restriction of women’s rights.

Cady Stanton’s goal was to provide a different perspective of the Bible—one that recognized the opinions of women and celebrated women as equals.

Despite heavy opposition, The Woman’s Bible became a bestseller—and while many scholars never accepted it, it has had a lasting influence on feminist theology.

Prominent feminist theologians like Mary Daly, Phyllis Trible, and Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza have drawn inspiration from The Woman’s Bible. In fact, Schüssler Fiorenza wrote Searching the Scriptures in 1993 to honor the 100th anniversary of the text.

Members of more progressive religious groups still discuss the book today, incorporating its insights into their own theological worldviews.

—Jenna Michelle, January 30,2024, in obscurehistories.com

The Woman’s Bible was controversial even within the women’s suffrage movement at that time, particularly because there was a political concern that it would harm the cause of women’s suffrage. It was viewed as an attack on traditional religious beliefs.

Opponents, particularly Carrie Chapman Catt (1859-1947) who was president of the National American Women’s Suffrage Association (NAWSA), used these fears for their political attack against Cady Stanton and the revising committee, calling them anti-religious.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton was eventually ostracized from within the feminist movement. She was pushed out of NAWSA and refused further involvement in that organization.

Here are two videos, just slightly over one minute each:

YouTube Video on The Woman’s Bible

Museum of the Bible, March 1, 2021

Note: If necessary, to access video page, override password request by clicking X in upper right of pop-up box.

Ever heard of the Women’s Bible?

by Nicola Russell

YouTube Nov, 14, 2024

Theologian Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza devoted pages 7-14 to The Woman’s Bible in her 1986 book, In Her Memory Her.

Schüssler Fiorenza’s discussion in her book on the political aspect of Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s insight is worth quoting here:

…[T]he Bible…[was] used in the trial of Anne Hutchinson (1637), [and had as] its function the legitimization of societal and ecclesiastical patriarchy and of women’s “divinely ordained place” in it.

Trial of Anne Hutchinson

The Women’s History Museum has on its website, this description of Anne Hutchinson’s “crime”:

Considered one of the earliest American feminists, Anne Hutchinson (1591-1643) was a spiritual leader in colonial Massachusetts who challenged male authority—and, indirectly, acceptable gender roles—by preaching to both women and men and by questioning Puritan teachings about salvation.

But the real issue was her defiance of gender roles—particularly that she presumed authority over men in her preaching. At a time when men ruled and women were to remain silent, Hutchinson asserted her right to preach, which her husband avidly supported.

The real issue to those in power was that she dared to overstep her place as a woman, and they feared she would likewise inspire other women to rebel.

—”Anne Hutchinson,” edited by Debra Michals, PhD, 2015, Women’s History Museum

Anne was excommunicated from the Massachusetts Bay Colony. She eventually moved with her family, after the death of her husband, to New Netherland (now New York). She and all but one of children were killed in the Pelham Bay area by the local natives in August 1643.

The National Park Service has more of her story.

Fun Fact: The Hutchinson River and Hutchinson River Parkway are named after Anne. The river is a 10-mile long stream in southern Westchester County, NY. The parkway (known colloquially as “the Hutch”) follows the river, extending from the Throggs Neck section of The Bronx to the New York-Connecticut state line at Rye Brook.

Returning to In Memory of Her, Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza wrote that Cady Stanton outlined three arguments why a scholarly and feminist interpretation of the Bible is politically necessary:

Throughout history and especially today the Bible is used to keep women in subjection and hinder their emancipation.

Not only men but especially women are the most faithful believers in the Bible as the word of God. Not only for men but also for women the Bible has a numinous authority.

No reform is possible in one area of society if not advanced also in all other areas. One cannot reform the law and other cultural institutions without also reforming biblical religion which claims the Bible as Holy Scripture.

Since all reforms are interdependent, a critical feminist interpretation is a necessary political endeavor, although it might not be opportune.

If feminists think they can neglect the revision of the Bible because there are more pressing political issues, then they do not recognize the political impact of Scripture upon the churches and society, and also upon the lives of women.

Schüssler Fiorenza also pinpointed two key insights of Elizabeth Cady Stanton:

Biblical interpretation is a political act.

…[T]he Bible is not just misunderstood or badly interpreted, but…it can be used in the political struggle against women’s suffrage because it is patriarchal and androcentric.

Backstory to #2:

....The Woman’s Bible was opposed not only because it was politically inopportune, but also because of its radical [interpretative] perspective which expanded and replaced the main [defensive] argument of other suffragists that the true message of the Bible was obstructed by the translations and interpretations.

Cady Stanton would agree that the scholarly interpretations of the Bible are male inspired and need to be ‘depatriarchalized.’

By…denying divine inspiration to the negative biblical statements about women, she claims her committee has shown more reverence for God than have the clergy of the church.

[She held that] every biblical passage on women must be carefully analyzed and evaluated for its androcentric implications.

In her autobiography Cady Stanton explains that she initiated the project because she had heard so many ‘conflicting opinions about the Bible, some saying it taught women’s emancipation, and some her subjection.’

Since she wanted to know what the ‘actual’ teachings of the Bible were The Woman’s Bible took the form of a scientific commentary on the biblical passages speaking about women.

This [critical]-topical approach has dominated and still dominates scholarly research and popular discussion of ‘Woman in the Bible.’

And so…

Fast forward to around three-quarters of a century later—to Third-Wave feminism and those biblical scholars and theologians whose writings were plentiful during that time.

They complemented and continued the work that Elizabeth Cady Stanton had started.

It is amazing what a gap of about 80 years will permit!

—Letty M. Russell (1929-2007)

THE LIBERATING WORD: A Guide to Nonsexist Interpretation of the Bible, Edited by Letty M. Russell (1977)

FEMINIST INTERPRETATION OF THE BIBLE, Letty M. Russell, Editor (1985)

—Rosemary Radford Ruether (1936-2022):

SEXISM AND GOD-TALK: Toward a Feminist Theology (1983)

—Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza (1938- ):

IN MEMORY OF HER: A Feminist Theological Reconstruction of Christian Origins (1983)

BREAD NOT STONE: the Challenge of Feminist Biblical Interpretation (1985)

BUT SHE SAID: Feminist Practices of Biblical Interpretation (1993)

SEARCHING THE SCRIPTURES: A Feminist Introduction,

Vol. 1,1993 - written for the 100th anniversary of The Woman’s Bible

SEARCHING THE SCRIPTURES: A Feminist Commentary,

Vol. 2 (1997)

—Phyllis Trible (1932- ):

GOD AND THE RHETORIC OF SEXUALITY (1978)

TEXTS OF TERROR: Literary-Feminist Readings of Biblical Narratives (1984)

OTHER THIRD-WAVE FEMINIST THEOLOGIANS OF NOTE:

(Works are listed in chronological order of publication date.)

Mary Daly (1928-2010): The Church and the Second Sex (1968)

Beyond God the Father: Toward a Philosophy of Women’s Liberation (1973)

Ada Maria Isasi-Diaz, Kwok Pui-lan, Katie Geneva Cannon, and Letty M. Russell, editors: Inheriting Our Mothers’ Gardens: Feminist Theology in Third World Perspective (1988),

Elizabeth A. Johnson (1941- ): She Who Is: The Mystery of God in Feminist Theological Discourse (1992)

Delores S. Williams (1937-2022): Sisters in the Wilderness: The Challenge of Womanist God-Talk (1993)

Eleanor Rae (1934- ): Women, the Earth, the Divine (1994)

A significant takeaway quote:

“Elizabeth Cady Stanton conceived of biblical interpretation as a political act."

—Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza, 1983

In Memory of Her, page 7.

To be continued…

Our next post will conclude the topic of the Women’s Movement, the first of our two-part series—by highlighting Fourth Wave Feminism, especially the views of young feminists.

IN YOUR WORDS:

—You are teaching us! —C.A.

— You are really writing a lot. It’s all wonderful! I feel that way every time I read a post! Well-written, thoroughly researched, thoughtful and inspiring posts every time!—M.W.

—I have to stop and tell you that what you are doing is so wonderful! —E.A.

—Thank you. —R.E.

—Good stuff. —E.R.

—New comment on THE ART OF WAKING UP into Second-Wave Feminism:

I am thinking of all the lives that were changed by your work! This is a perfect example of how a few people working together can make changes and create opportunities. This was so inspiring, and thank you for sharing your story!—M.I.

C:WED Wish List:

—Please remember us when you are thinking of making a charitable contribution.

—Do send us something related to our themes: Women, the Earth, and/or the Divine.

You may send it/them via:

—the CONTACT button below

—our email at info@cwed.org

—USPS mail delivery

—in person

—any other way you can think of. Pigeon?

—Maybe a quote, an article you think our readers would like, a poem, a prayer, a cartoon, a photo or video, a drawing or painting—or your own original essay?

—A resource recommendation?

—Or just a comment?

We have planned this series to explore two movements—the Women’s Movement and the Environmental Movement—as they exist, and are linked, in a patriarchal world.

We have revised our publishing schedule for this series to one post every week for the next few months.