UPON WHAT LAW? What was the legal source of coverture?

In a discussion we were having, Eleanor raised the question: upon what law was coverture based? Since the term coverture, on which I had reported in my previous post, was a new one for both of us, it required some research. This post attempts to address that question.

It seems to me that focusing on this question on Valentine’s Day is coincidentally perfect timing! These laws of coverture, after all, have been directly related to the relationship between husbands and wives (or in the case of young lovers: potential husbands and wives).

Recap from my last post:

What was coverture?

Coverture was the law of the land that made married women little more than the property of their husbands.

Coverture was the legal doctrine that treated a married woman’s possessions, wages, body, and children as property of her husband, available for him to use as he pleased.

Coverture gave husbands total control—from finances and place of residency to wife-beating and marital rape. A wife, as Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote during the Seneca Falls Convention, was “compelled to promise obedience to her husband, he becoming, to all intents and purposes, her master.”

Coverture held that no female person had a legal identity.

[For] at birth, a female baby was covered by her father's identity, and then, when she married, by her husband's. The husband and wife became one—and that one was the husband. As a symbol of this subsuming of identity, women took the last names of their husbands.

Why does it matter to know about these laws?

It matters to know:

That married women in America had lived under such restrictive conditions that effectively made them the property of their husbands—and that men in the U.S. had embraced it.

That there are vestiges of coverture in existence today—and to begin to learn how to recognize them.

To be vigilant about any current top-level attempts to haul women (and men) back to those times.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND:

Coverture is a long-standing legal structure that is part of our colonial heritage. Though Spanish and French versions of coverture existed in the new world, United States coverture is based in English law. (Catherine Allborg)

Coverture was a legal doctrine in English common law originating from the French word couverture, meaning "covering", in which a married woman's legal existence was considered to be merged with that of her husband. Upon marriage, she had no independent legal existence of her own.

Following are excerpts taken from the treatise by E. H. DEERING, J.D. student , Washington University School of Law:

“Coverture and Lasting Effects of Gender Inequality: An Analysis Through Equal Protection Jurisprudence.”

The unequal treatment of women predated the formation of America by way of the common law doctrine of ‘coverture’, which can be traced back to England in the Middle Ages.

During the Middle Ages, coverture ‘“adhered to the biblical principle that a husband and wife were ‘one flesh’ represented legally by the husband as the head of the household.” (Sara Butler)

Common law coverture changed very little from the twelfth century through the late nineteenth century in Europe.

Historically, coverture was validated as a legal principle in 1765 -1769 by Sir William Blackstone’s ‘Commentaries on the Laws of England,’ an influential treatise that outlines English ‘common law’ into a system of legal principles. They were informally known as Blackstone’s Commentaries.

Blackstone’s treatise outlined the consolidation of the husband and wife into one legal entity, where the husband controls the power of the legal entity.

MOVING TO AMERICA

Deeply rooted in English common law, American law adopted the idea of coverture at its founding.

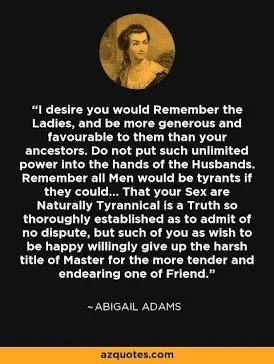

Abigail Adams in 1776 attempted to make a change when she wrote to her husband John Adams while he was in Philadelphia working with the Continental Congress. In her famous letter, she implored him to “Remember the Ladies,” seeking to eliminate the restrictions on married women under coverture. Her plea went unheeded and nothing changed for women during the American Revolution.

Explicit coverture was partially dismantled through legislation throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

The same social movement that pioneered women’s suffrage also pushed for the end of coverture. …[W]ith the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment on August 26, 1920, women not only gained the right to vote but now also had the right to participate fully in political life.

This rebut[ted] the heart of the rationale for coverture: that women’s role in society lay solely in the domestic sphere of home and marriage.

Although coverture was being legally dismantled, coverture-adjacent legislation and beliefs continued to dominate the lives of women in the U.S.

EXAMPLE OF COVERTURE-ADJACENT LEGISLATION:

For example, economic freedom for American women was greatly limited until the 1970s. Before the passing of the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, women were not guaranteed to be free from discrimination based on their gender when applying for credit.

Many insidious doctrines based on the doctrine of coverture have permeated our legal system for centuries and have yet to be formally overruled.

[My comment: while it took the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), which was proposed in 1923 and updated by Alice Paul in 1943, almost 100 years to receive the required 38 state ratifications in 2020, it has still not been certified as the 28th Amendment to the Consitution. The future of the Amendment, which is central to the ongoing struggle for equality, is uncertain due to pending legal challenges.]

____________________________

A STORY ABOUT A VESTIGE:

Historian Catherine Allgor demonstrates a vestige of coverture with a personal story in her 2012 essay, “Coverture: The Word You Probably Don’t Know But Should”

My mother-in-law loves this story. A few years ago, my husband, Andrew, and I went to apply for a mortgage. As a candidate for a house mortgage—and this is the part my mother-in-law loves—I characterize myself as “greater” than my husband.

I am older, I have a longer work history, I am more senior in our common profession (we are both professors), I also make more money. I’ve got a longer credit history than he and have owned more houses. Finally (though this is a matter of dispute), I am even a teeny bit taller.

But the only qualification that mattered in this transaction was my status as “wife.” When our broker filled out our application, she listed Andrew first, as the “borrower” and me second, as “co-borrower.” (Did I mention that my last name starts with “A” and his with “J”?).

When I pointed this out, our broker, a woman of a certain age with long experience in her profession, sympathized, but stated that if she had made me the primary borrower, the lawyers would “fuss” at her and just revert to the traditional categories.

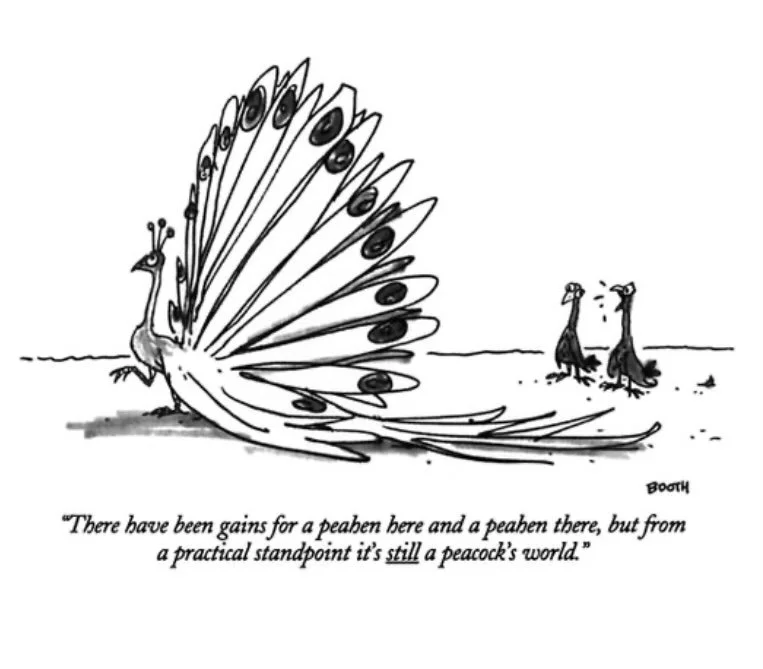

“Honey,” she told me, a professor of women’s history, “it’s a man’s world.”

Point taken. What I had just encountered was a vestige of the legal practice of coverture.

…To be continued

NOTE!

WE NEED TO SWITCH TO SENDING THIS SERIES OF EMAILS TO ONE A WEEK FOR THE NEXT MONTH OR SO.

OUR CURRENT FUNDS ARE LIMITING US TO UPGRADE TO ONLY ONE HIGHER LEVEL FOR EMAIL SERVICE.

Would you conider helping us with a tax-deductible donation?

We plan an exploring two movements—the Women’s Movement and the Environmental Movement—as they exist, and are linked, in a patriarchal world.

Our Wishes:

We are hoping for a guest writer, or more, on the subjects of women and the Earth in a patriarchal world! Could this be you?

Do you have something to say that we might publish in a post?

Perhaps you have a new perspective?

Perhaps from a diverse culture?

Maybe: a short essay, a prayer, a poem, a drawing, a cartoon, a resource that you would like to suggest on these topics?